1. Regulations and crackdowns

The Chinese Government has been cracking down on a few different technology-related industries recently. We’ve noted previously Ant Financial, Didi, and the online tutoring industry. And now, it is “targeting” food delivery companies by forcing them to focus more on labour rights. We know that the CCP likes to take credit for cracking down on companies that violate labour laws while at the same time penalising workers who organise among themselves.

Many have questioned the motives of this crackdown on technology industries. Is it purely political? Is it because Big Tech is threatening the “monopoly” power of the CCP?

On one level, all regulations are inherently political. Antitrust laws and monopoly regulations are about disciplining and regulating big businesses. As companies become bigger and more powerful, they have more influence over society as well as the behaviour and decision-making of individuals. And that can come at the expense of the influence of governments.

Until recently, the power of big companies appeared to be on the rise, with multinational companies choosing to locate their production where there are minimal regulations, and different jurisdictions competing for the big companies to locate there. Deregulation was in vogue.

But in the last decade, the power of the state has struck back, with neoliberal orthodoxy seemingly on the retreat. People look to governments to do more to regulate companies and protect them from labour abuses or environmental damages wrought by the companies. And industry policies are now commonly accepted.

For tech industries in particular, due to how fast it has grown and how pervasive it has become in everyone’s lives, government regulations have often not kept up to its spread and its importance. While this is great for innovation, people are also becoming concerned about the social costs.

So it is in this context that the Chinese Government is regulating or cracking down on its tech companies. According to Alan Song, “Chinese entrepreneurs and investors must understand that the age of reckless capital expansion is over. A new era that prioritises fairness over efficiency has begun.”

But it may also be more than just regulation, and the timing of the decisions around Ant and Didi seems to suggest that. The CCP (like governments almost anywhere) wants to harness the power of the big tech companies (and the data they hold) for its own purposes. And it wants to ensure the power of the private sector never encroaches on the power of the state. Compared to most democracies, it has more tools at its disposal to ensure that.

So now China is seriously regulating its tech industry, will the US do more in this regard too? After all, one of the arguments put up by the US companies for resisting regulation is that regulation will constrain their growth and they will be less competitive than Chinese companies who are supported by the CCP.

2. Leader visits

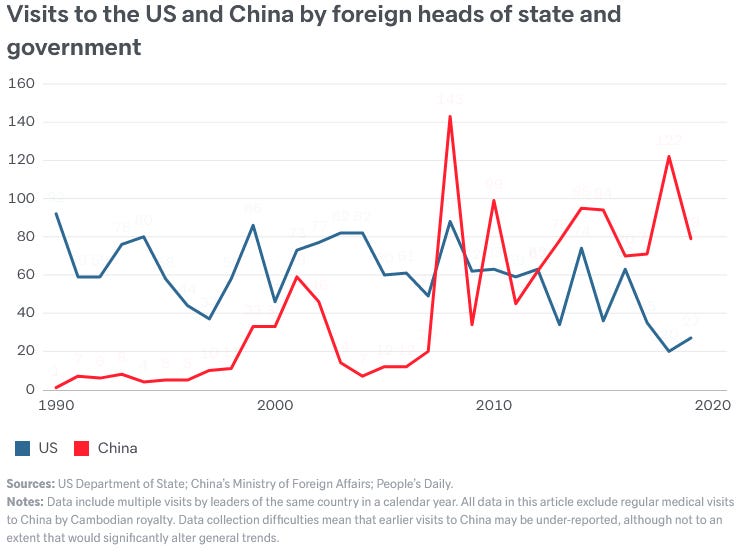

Neil Thomas’s recent work compared world leaders visiting China to visiting the US. He found that:

In 2019, the year before Covid-19 halted most travel, 79 foreign leaders visited China, while only 27 called on the United States. More world leaders have visited China than the United States in every year since 2013, a sharp turnaround from the American dominance of the early post-Cold War era.

On regional breakdowns:

In the 2010s, compared to the United States, China received more than triple the number of visits by Asian and Oceanian leaders, more than double the number by African leaders, and almost double the number by Eastern European leaders. Even leaders from North and South America, the US’s diplomatic backyard, slightly preferred China. Only Middle Eastern and Western European leaders made more trips to the United States.

Do read his entire article, which also includes interesting graphs and tables, such as this one:

As you can see, he sourced data from the US Department of State, China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and People’s Daily. It shows what interesting research we can do just from using such accessible data.

Even in the age of online multilateral meetings, leader visits are still important. “Guests of Government” visits require the coordination of multiple federal departments and ministers. They are usually an impetus for bureaucrats and ministers to come up with initiatives (or “announceables”) aimed at fostering cooperation between the two countries. Without such push, governments tend to revert to business as usual of managing relationships.

These visits must be planned and agreed upon in advance by both countries. The smaller number of visits to the US is unlikely reflective of demand — most world leaders would like to visit the US, which remains the most powerful country. Rather, I think it’s more reflective of supply — protocol dictates that leaders must meet their counterpart, the President, and the US President may prefer to spend more time focusing on domestic affairs, for example (or in Trump’s, perhaps golf?).

It makes sense for the Chinese Government to focus on diplomacy. China cannot compete with the US on military power (e.g. foreign bases and deployments) or in soft power. And it understands that in multilateral forums such as the UN, having more friends, no matter how small they are, is important.

3. Asia capability in Australia

Australia is investing less in Asia-capability just as Asia has become more important to Australia and the world. One crucial part of investing in future Asia-capability is spending on schools and higher education in Asia-relevant fields, especially the study of Asia’s history, language, and culture.

In the Lowy Institute report on Chinese-Australians in the Australian Public Service (APS), published in April this year, I wrote:

Last decade, Australia spent the least amount of time of all OECD countries teaching a second language to its students. The proportion of students studying a foreign language in Year 12 decreased from 40 per cent in 1960 to around 10 per cent in 2016. The situation with Chinese language study is not much better, with students eschewing Chinese as a second language at Year 12 and university level in Australia.

In response to a survey by Asian Studies Association of Australia, one academic noted: “We have seen the gradual hollowing out of the deep language and cultural expertise on China in Australia. Increasingly those Australians who speak to us about China don’t know the language, nor have they spent extended time studying its history, culture and politics.”

I also noted that language skills are important but insufficient:

It is not enough to rely on translations of official documents or the words of a spokesperson from China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Reading these is a good and important start, but a greater understanding of China generally — from its customs to its statecraft — is necessary to interpret them. Without those additional layers of understanding and interpretation, the risk of misunderstanding is high.

With understanding Asia so important for Australia, it seems strange that Asian studies programs are being decimated in some Australian universities. For example, the University of Western Australia is moving the Asian studies program to teaching only (no research), after cutting its Indonesian language program. La Trobe has cut Indonesian and Hindi (leaving ANU the only university teaching Hindi in Australia), as well as downsizing its Asia research and engagement program. I feel lucky that ANU has continued to support classes with small enrolment, including in Literary Chinese, which I have been studying for the past year.

The attitude to “regional studies” also partly reflects Western-centric thinking. Some in international relations or strategic studies assume that theories developed in the West can be easily applied to other countries or cultures. Therefore, we don’t need to understand other countries or their languages and cultures — people with expertise in national security but little knowledge of China are frequently asked to comment on China’s policies, intentions and even cultures.

What does it mean for Australia’s future? Even though we like to remind other countries (especially the US and European countries) that we are in the region, culturally we are resistant to this. Due to the lack of investment in training future Asia-capable workforce, Australia may have to rely even more on Asian Australian migrants for their Asia capabilities.

But barriers and challenges remain (detailed in my Lowy report), as many Australian organisations (including the public service) still have monocultural and monolingual biases. Prof Louise Edwards noted this phenomenon of under-valuing linguistic and cultural knowledge:

they don’t have a multilingual consciousness. By the latter I mean that it is possible for people to only have one language, but to have some understanding of how this limits them, how to appreciate the language labour others are undertaking in communicating with them in their one language, and even how to work effectively with interpreters. Many of our leaders have neither multilingualism or multilingual consciousness—hence the slashing and burning of foreign language and culture courses in universities in recent decades on the basis that they are “too expensive”. [...]

Well, my students are not thrilled about this. They are creative, multilingual, innovative, energetic, empathetic, globally aware and unless they get invited into the heart of organisational policymaking, agenda setting, and listened to while they are there, I fear that they will take their great ideas and head out of Australia, to Asia, where they will be heard. Their cross-cultural skills will be valued rather than ignored, or regarded with suspicion.

Neican Brief is made possible by the support of the Australian Centre on China in the World, Australian National University.