China Neican: Party history, Hua Guofeng, rural issues, heroes and martyrs

26 February 2021

Subscribe to Necian and join thousands of policymakers, researchers, and business and media professionals. If you are already a fan, please spread the word:

1. Studying Party history

Last week we wrote about the upcoming 100th anniversary of the CCP in July, and the importance of current and historical narratives for the Party’s rule. As we mentioned, this includes what the Party calls the “four histories” (histories of the CCP, “New China”, reform and opening up, and development of socialism).

The CCP’s focus on the “four histories” highlights the politicised way in which official history is constructed and used in China. In short, the Party wants to shape what is remembered, what is forgotten, and what lessons are learnt from the past.

Official history in China today is crafted and propagated to serve the interests of the ruling power. Official history lionises the Party, and enforce collective amnesia with respect to the Party’s failings, including costly policy failures.

Moreover, the official version of history puts the Party at the heart of the historical process. In the Party’s narrative, its current monopoly on power was the result of an inevitable historical process, one that follows the rules of Marxist dialectical materialism. In this narrative, the Party is leading the Chinese nation towards inevitable greatness.

Today, let’s look a bit more at the most sacred of the “four histories”: Party history.

Party history is seen by the Party leadership as especially important this year, in the lead up to the centenary of the CCP’s founding. The Party has just launched a new campaign to learn party history. Unlike efforts to promote the “four histories,” the current campaign is targeted internally at Party members. At the mobilisation meeting kicking off this new campaign on February 20, Xi gave three key reasons for Party members to study Party history:

The first is to use the Party's struggle and great achievements to inspire and clarify its direction; the second is to use the Party's glorious traditions and fine style to strengthen beliefs and gather strength; and the third is to use the Party's practical creation and historical experience to enlighten wisdom and sharpen character.

一是用党的奋斗历程和伟大成就鼓舞斗志、明确方向,二是用党的光荣传统和优良作风坚定信念、凝聚力量,三是用党的实践创造和历史经验启迪智慧、砥砺品格。

The current mobilisation effort is not so much about the past as it is about preparing the Party for future challenges. In Xi’s words:

We should seize the opportunity given by the occasion that is the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Party. We should summarise and apply the Party’s rich experience of successfully dealing with risks and challenges in different historical periods. This would prepare our minds and work to deal with changes in the external environment for a relatively long period of time. We should constantly enhance our awareness of struggle, enrich our experience through struggle, improve our skills through struggle, and constantly improve our capability of governance.

习近平强调,要抓住建党一百年这个重要节点...总结运用党在不同历史时期成功应对风险挑战的丰富经验,做好较长时间应对外部环境变化的思想准备和工作准备,不断增强斗争意识、丰富斗争经验、提升斗争本领,不断提高治国理政能力和水平。

In arguing for the importance of studying Party history in the current juncture, Xi alludes to the potential disaster consequence of disunity without explicitly referring to past periods of disunity:

It is important to educate and guide the entire party to learn from both positive and negative historical experiences from the history of the party, to unswervingly align with the party central committee; to constantly improve political judgment, political comprehension and political execution; to consciously maintain a high degree of consistency with the party central in ideology, politics and action; and to ensure that the entire party is united in a single thread, with one mind and one strength...

The party's unity and centralised unity is the life of the party, and is the key to our party's success in becoming a century-old party and creating a century of greatness. This is also the key to learning and educating about the history of the Party.

要教育引导全党从党史中汲取正反两方面历史经验,坚定不移向党中央看齐,不断提高政治判断力、政治领悟力、政治执行力,自觉在思想上政治上行动上同党中央保持高度一致,确保全党上下拧成一股绳,心往一处想、劲往一处使...

旗帜鲜明讲政治、保证党的团结和集中统一是党的生命,是我们党能成为百年大党、创造世纪伟业的关键所在。这也是党史学习教育的关键所在。

(emphasis added)

Xi hopes to strengthen the unity and ideological belief of the Party rank and file by aligning their historical understanding. But equally important, this campaign is about securing his position as the paramount leader, the core of the core, without which the Party will supposedly be directionless, and even plunged into crisis. The quote above essentially urges Party members to be loyal to the Party Centre, that is, to the team led by Xi himself.

Xi didn’t have to mention the Cultural Revolution and the 1989 Tiananmen protests to his audience. But both will be at the forefront of their minds in thinking about the lessons of the past.

For those of us watching political developments in China, changes in how the Party looks at the past is highly relevant for the present. Here is a timely example...

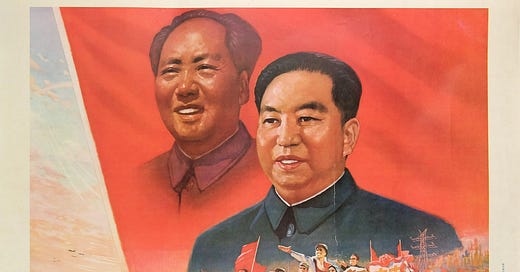

2. Praising Hua Guofeng

Remembering the dead is not so much for the dead as it is for the living. This is especially the case with dead Party leaders.

On February 20, the CCP held a high profile symposium to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the birth of Hua Guofeng (纪念华国锋同志诞辰100周年座谈会). This event was attended by two Politburo Standing Committee members: Wang Huning and Han Zhen.

For those of us that need to be reminded who Hua is...

Hua Guofeng took over as the Party’s top leader following the death of Mao, and arrest of the Gang of Four in late 1976. By 1980 he was outmaneuvered and sidelined by Deng Xiaoping who Hua helped to rehabilitate. Hua was eased out of power, and died in August 2008.

After Hua’s exit from the political limelight, he was seldom mentioned publicly by the Party. It was not in Deng’s interest for Hua’s shadow to linger in Chinese politics because that would erode his legitimacy as the paramount leader. For Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao, there was little reason to remember Hua because doing so would destablise the mythology surrounding Deng.

At the symposium on Hua, Wang Huning, the Party’s chief ideologue and 5th ranking member of the Politburo Standing Committee, praised Hua in glowing terms and linked Hua’s virtues with the demand for Party members to unite around Xi:

We commemorate Comrade Hua Guofeng to learn his political character of being firm and loyal to the Party, his deep conviction of sticking to his original mission and caring for the people, his fine style of being practical and realistic, and his noble quality of being open and honest and self-disciplined. In the new journey of building a modern socialist country, we must adhere to Xi Jinping's thought of socialism with Chinese characteristics in the new era as a guide...unite closely around the Party Central Committee with Comrade Xi Jinping at the core, overcome difficulties, pioneer and innovate, dare to fight and be good at fighting, and strive to create new performance worthy of the times, the people and our forefathers, so as to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the founding of the CCP with outstanding achievements.

我们纪念华国锋同志,就是要学习他党性坚定、对党忠诚的政治品格,坚守初心、心系人民的深厚情怀,求真务实、真抓实干的优良作风,光明磊落、清廉自律的高尚品质。在全面建设社会主义现代化国家新征程上,我们要坚持以习近平新时代中国特色社会主义思想为指导...紧密团结在以习近平同志为核心的党中央周围,攻坚克难,开拓创新,敢于斗争,善于斗争,努力创造更加无愧于时代、无愧于人民、无愧于先辈的新业绩,以优异成绩庆祝中国共产党成立100周年。

This is the first time since Hua’s ousting that the CCP leadership has spoken of Hua publicly and in such flattering terms. It illustrates that the evaluation of historical events and personalities can change depending on political necessity.

In Xi’s case, taking Hua out of the freezer of Party history and praising him serves three purposes. First, lauding Hua’s political loyalty is a clear message to Party cadres to be loyal themselves to Xi. Hua, of course, was commonly seen as a loyal servant of Mao. As the successor of Mao, he had (in)famously advanced the “Two Whatevers” (两个凡是): “We will resolutely uphold whatever policy decisions Chairman Mao made, and unswervingly follow whatever instructions Chairman Mao gave” (凡是毛主席作出的决策,我们都坚决维护;凡是毛主席的指示,我们都始终不渝地遵循).

But Hua was also instrumental in challenging Mao’s legacy. Together with Marshal Ye Jianying and others, he plotted and carried out the arrest of Mao’s ideological successors, the Gang of Four. So, the history of Hua is more ambivalent than commonly understood.

Second, raising the profile of Hua serves to reduce the status of Deng in the pantheon of CCP’s greats. To raise Xi’s prestige, Deng had to be taken down a notch. Indeed, in recent years, we have seen a gradual reduction in the status of Deng in Party historiography. In effect, Deng is now often portrayed as the one that set up the stage for the real star (Xi) and the real play (national rejuvenation).

Third, the high profile celebration of the life of Hua can be seen as a symbolic rejection of what Deng has been criticised (and indeed, praised) for: ideology-free pragmatism. Deng was famous for his saying: “It doesn't matter whether a cat is black or white, as long as it catches mice.” In the era of Xi, the colour of the cat matters, and that colour should be red.

The celebration of the centenary of Hua's birth (February 16) juxtaposes with the non-celebration of Deng’s death anniversary this year (February 19).

3. Rural issues and food security

The CCP Central Committee and the State Council jointly released a new policy document on rural revitalisation and agriculture modernisation (关于全面推进乡村振兴加快农业农村现代化的意见) recently. This document articulates China’s priorities in the agriculture sector for the 14th Five Year Plan (2021-2025).

The document is also known as “Central Committee #1 Document”, as it is the first document of the year released by the Central Committee and the State Council. The “#1 Document” for every year since 2004 has been on rural issues, signalling the importance placed on these issues by the CCP. After all, the CCP came to power largely on the back of the support of rural peasants, and one of its most important policy platform was land distribution (土地改革运动).

The policy documents referred to “Three Rural Issues” (三农): agriculture production, rural development, and peasant income (农业、农村、农民).

For those outside China and keen to understand how this can affect their own countries in the next few years, perhaps the most relevant parts of the document are those on agriculture production and food security. How much and what China produces will affect how much and what it imports, and in turn, affect the politically sensitive agricultural sectors in exporting countries.

One of the priorities under “agricultural modernisation” is improving the supply guarantee of important agricultural products (提升粮食和重要农产品供给保障能力). Specific products mentioned under this include rice, wheat, maize, soybeans, canola and peanut, pork, beef, lamb, and dairy.

In terms of links to the international market, it is mentioned with reference to “import diversification” of agricultural products (实施农产品进口多元化战略) and “supporting companies’ integration into the global supply chain” (支持企业融入全球农产品供应链). It also mentioned combating smuggling and strengthening quarantine.

Food security is very important for China. Throughout history, regime (in)stability has often been linked to famine. In the current geopolitical climate, the CCP is likely worried that possible future trade restrictions could affect food security, as China is a net importer of food. In the past few years, emphasis on domestic supply has noticeably increased, while the language around imports has become more cautious. So we should expect more protections for China’s agriculture sector.

China is not the only country protecting its agriculture industry. Developed countries, including the EU, Japan and the US, as well as developing countries, such as India, all protect their agricultural sectors in some ways. Famously, agriculture was the big sticking point that led to the stalling of the WTO Doha Round. China’s commitment to purchase more US agricultural products was also the central part of Trump’s touting for the “Phase One” deal.

It is also interesting to note that while countries such as Australia are hotly debating “export diversification”, China is striving for “import diversification” in agriculture. Depending on market composition (the number and size of suppliers and purchasers), it would be easier to diversify in some sectors than for others. Generally however, it’s easier for a bigger economy to diversify trade than for a small economy to diversify trade away from bigger economies.

4. “Patriotic” social media crackdown

Chinese authorities have detained at least six people for “defaming martyrs” who died in the Galwan Valley border clashes with India. One of the people being sought by the authorities is only 19 and lives outside China, where he presumably posted the offending comments. In 2018, China passed a law making it illegal to slander the country’s current and past “martyrs”.

In authoritarian countries (and countries trending to authoritarianism), there is only one “correct” version of history, and one “correct” version of truth. Any deviation of this official or “correct” version is met with potential punishment.

In more open and liberal societies, questioning of historical and contemporary events can still be very controversial (e.g. moral responsibility for civilian casualties in WWII). While such controversy can create overwhelming social pressure for people to stay silent on certain issues, by and large they do not have to face the additional legal pressure to censor themselves.

We regularly emphasise the importance of history to the CCP. It is imperative for the CCP that the sacrifice of the past and present “heroes and martyrs” has meaning. It can serve two purposes. One, it makes people more grateful for the government and the military, and fosters a sense of national identity and unity. Two, it incentivises people to continue to make sacrifices, in hope that they too can be immortalised as “heroes and martyrs”.

In terms of censorship itself, it’s not surprising that what’s posted online can land you in trouble in China. This has been going on for a while, including most famously with Dr Li Wenliang last year. It is also not the first time that China has pursued someone for comments posted while they were overseas, and that is something to bear in mind for those who criticise China online and intend to visit China later.

A former employee with ByteDance (owner of TikTok) who worked on content moderation spoke with Shen Lu:

The truth is, political speech comprised a tiny fraction of deleted content. Chinese netizens are fluent in self-censorship and know what not to say. ByteDance's platforms — Douyin, Toutiao, Xigua and Huoshan — are mostly entertainment apps. We mostly censored content the Chinese government considers morally hazardous — pornography, lewd conversations, nudity, graphic images and curse words — as well as unauthorized livestreaming sales and content that violated copyright.

But political speech still looms large. What Chinese user-generated content platforms most fear is failing to delete politically sensitive content that later puts the company under heavy government scrutiny. It's a life-and-death matter. Occasionally, ByteDance's content moderation system would go down for a few minutes. It was nerve-wracking because we didn't know what kind of political disaster could occur in that window. As a young unicorn, ByteDance does not have strong government relationships like other tech giants do, so it's walking a tightrope every second.

China Story

Osmond Chiu, Negative feelings towards Chinese immigrants show our debates do not happen in a vacuum: The Scanlon Foundation’s annual Mapping Social Cohesion report found widespread negative feelings towards immigrants from China. It has implications for how Australia discusses matters involving China and Chinese people as there may be unintended consequences. Further research is urgently needed to understand the cause of these negative sentiments and how to address this complex problem.

Séagh Kehoe, China, Tibet and the Politics of Time:The politics of time are an important dimension of Chinese state discourse about Tibet, yet one that has received relatively little attention to date. This piece examines the written and visual discourses about Tibet’s past, present and future across Chinese state media in the post-2008 era. The focus is on how these media discourses attempt to construct a very particular system of storytelling about the passage of time in Tibet in order to consolidate Chinese rule over the region. It also considers the ways in which new media practices have enabled the production and reproduction of Chinese state power over Tibet.

Chinoiserie

Playing at War Games with China — Remarks by Ambassador Chas W Freeman: Our China policy should be part of a new and broader Asia strategy, not the main determinant of our relations with other Asian nations or the sole driver of our policies in the region. And to be able to hold our own with China, we must renew our competitive capacity and build a society that is demonstrably better governed, better educated, more egalitarian, more open, more innovative, and healthier as well as freer than all others. To paraphrase Napoleon, let China take its own path while we take our own. We need to fix our own problems before we try to fix China’s. If we Americans get our priorities right, we can once again be the nation to rise and astonish the world.

Mara Hvistendahl, How Oracle Sells Repression in China: In its bid for TikTok, Oracle was supposed to prevent data from being passed to Chinese police. Instead, it’s been marketing its own software for their surveillance work.

"Subscribe to Necian "?