China Neican: monopoly, public opinion, women in leadership, sent-down youth

28 December 2020

China Neican is a newsletter by Yun Jiang and Adam Ni from the Australian Centre on China in the World, and the China Policy Centre in Canberra. The newsletter is also published as a weekly column on the China Story blog. The name Neican 内参 (“internal reference”) comes from limited circulation reports only for the eyes of high-ranking officials in China, dealing with topics deemed too sensitive for public consumption. To receive regular updates, please subscribe. You can find past issues here.

1. Alibaba

China’s State Administration for Market Regulation (SAMR) 国家市场监管总局 announced that it was investigating possible monopolistic practices by Alibaba. These alleged practices include Alibaba’s tactic of pressuring merchants to sell exclusively on its platform.

The current investigation is the first of its kind against a Chinese internet company. It comes a month after Chinese authorities scuttled Alibaba affiliate Ant Financial’s $37 billion IPO at the last minute. Announcement of the investigation into Alibaba also coincided with further bad news for Ant. Chinese regulators on Sunday accused the fintech giant of unsound corporate governance practices, inadequate compliance with regulations, anti-competitive behaviour, and harming consumer interests. Ant has been ordered to address these issues as well as meet capital requirements through corporate restructuring.

Anti-monopoly efforts have become a priority issue for the Chinese government in recent months. Shortly after Beijing vetoed the Ant IPO, SAMR released a set of draft guidelines against monopolistic behaviour by internet platforms. In addition, Xi pointed out the importance of anti-monopoly efforts for intellectual property protection at a recent Politburo study session.

This was followed by the Politburo meeting of December 11, which discussed economic policy for 2021. Readout from the meeting mentioned the need for China to “strengthen anti-monopoly work and prevent disorderly capital accumulation 强化反垄断和防止资本无序扩张”. This is the first time that such language has been adopted at the top political level. At the Central Economic Policy Work Conference that ran from December 16 to 18, this task was listed as one of the eight economic policy priorities for 2021.

In short, Beijing has signalled that it’s going to ramp up scrutiny of Chinese internet companies. The question was when and how the authorities would go after the dominant players, Alibaba and Tencent.

Why is Beijing doing this?

First, tightening regulation over China’s internet and tech companies fits within the broader trends towards tighter party control over the economy. For Xi, Marxist political economy has enduring relevance for China, including the importance of state dominance in economic activities. Beijing’s new zeal against monopolistic practices does not seem to extend to state-owned enterprises. Certainly, some of their activities deserve added scrutiny from a market competition perspective.

Second, internet platforms have become essential in the daily lives of most Chinese people, and yet they are thought to be under-regulated by policymakers. This is especially so because “super platforms” (such as WeChat) and fintech systems are powerful enough to pose substantial financial and political risks. Reining them in serves to mitigate risks, which is a top priority political and economic priority for Beijing.

Third, there is rising disgruntlement in China with the Alibaba-Tencent duopoly. In particular, concerns about stifling innovation and market competition have become stronger recently. For tech entrepreneurs, for example, Alibaba and Tencent’s dominant market positions, control of “super platforms”, and extensive influence and involvement in China’s tech startup sector, makes it very hard for them to flourish without the support of one or the other. Bytedance, the owner of Douyin/Tiktok, is one of the few exceptions that have managed to flourish without aligning itself with either Alibaba or Tencent.

There are certainly valid concerns about the market power of Alibaba and Tencent that deserve scrutiny. But we are not sure that Beijing’s high profile targeting of Alibaba, which will likely become more intense in the coming months, is the best way to deal with the problems. In any case, for many Chinese and international companies, this ongoing saga is yet another sign of the increased risk involved in doing business in China.

Beijing, like other governments, is working out how to regulate the tech sector with its various issues, including data usage and privacy, competition, and innovation. The difference is that China’s political economy is unique due to the role played by the CCP.

In essence, Beijing is trying to balance party control and state involvement in the economy with other considerations, such as market dynamism and confidence, and space for the private sector. This balance is increasingly tilting towards the state with long term implications for the prospects and structure of the Chinese economy.

2. Chinese public opinion

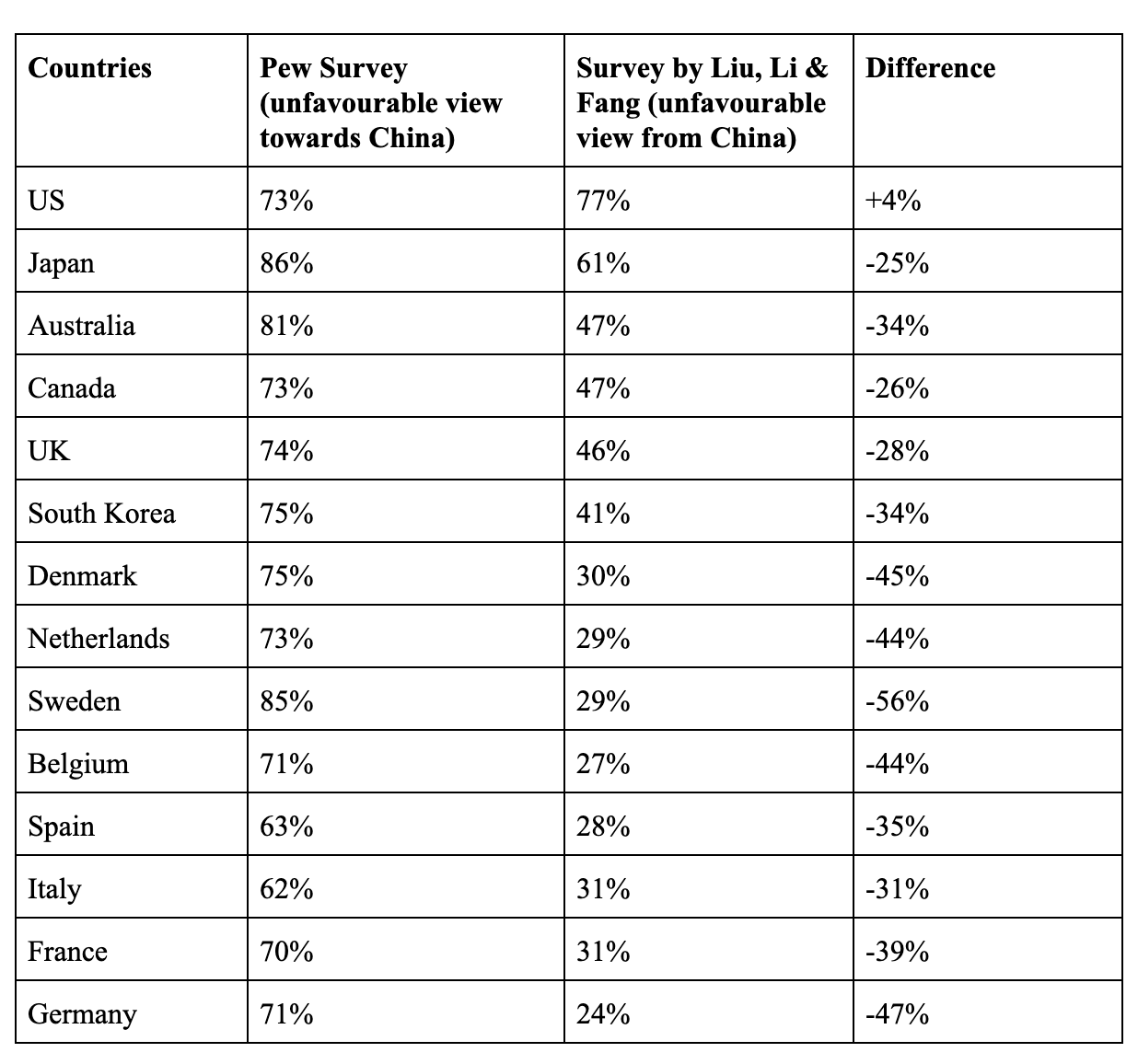

A June/July Pew survey found that public opinion of China has deteriorated sharply across 14 developed economies in recent years. But how about the other side of the story? How do the Chinese public view these 14 countries?

A new survey shows that the Chinese public holds less unfavourable views of these 14 countries than the other way around. With the exception of the US, the differences are significant. In Australia’s case, for example, 83 per cent of Australians held unfavourable views of China whereas only 47 per cent of Chinese held unfavourable views of Australia. For comparison, we have put the data from the two surveys into the table below.

How can these divergent views be explained?

One possible explanation is that most heat is drawn by the US. The Chinese public probably knows much more about US-China bilateral friction than Beijing’s row with other countries, such as Australia and Canada. This makes sense considering that most of Beijing’s rhetoric against foreign countries are pointed at Washington.

Another possible explanation is that perhaps with the exception of the US and Japan, the Chinese public may have held quite low levels of unfavourable views towards these other countries in the past. Diplomatic friction may have elevated antipathy, but not enough to make the level of unfavourable views held by the Chinese comparable to the Pew survey data.

One challenge in interpreting the data from the new survey is that, unlike Pew survey, it’s not a longitudinal study. This makes it difficult to identify changes to Chinese public sentiment.

On a related note, we may be seeing an increasing divergence between how the Chinese view China and how people in other countries see China. For instance, in a new Global Times Poll Center survey, 78 per cent of the Chinese respondents believed that China’s international image has improved in recent years. This belief does not match the recent survey data, at least not from developed economies and Southeast Asian countries.

One important implication of this mismatch in perceptions may be that the Chinese public’s support for Xi’s foreign policy is partly based on misconceptions of what the world thinks of China. If they believe that Xi’s approach to foreign policy is improving China’s image around the world, then they are more likely to support, or even advocate for, the kind of assertive diplomacy that has been ill-received by many countries.

3. Women in political leadership

The representation of women in political leadership positions is dismal in China. And the higher up it is the fewer women in these roles. There is only one woman in the 25-member Politburo. In contrast, Tsai Ing-wen made history in 2016 when she became Taiwan’s first female president.

According to Shen Lu, at the county level, women make up 9 per cent of the leadership, at the municipal level, 5 per cent, and at the provincial level, only 3 per cent. Moreover, women comprise only 27 per cent of CCP’s 92 million members.

These low figures partly reflect broader social attitudes towards women in the workplace and women in power, as well as the culture of the workplace in general.

As we have written previously, women never achieved true equality, despite the Party-state’s rhetoric under Mao. Since the start of the reform and opening up and with the declining state support in areas such as childcare, gender inequality has grown in some metrics, including labour participation and pay disparity.

Within China, the broader social attitude is still that women bear the primary responsibility for childcare and homemaking, roles that are devalued in society.

In the workplace environment, women still experience a high level of discrimination, from recruitment (including ads explicitly state a preference for men) to the culture of entertainment (应酬). From Shen Lu:

“If we are filling two positions that attracted one male applicant and four female applicants, as long as the man is not too disappointing, he is in,” says Liu, a low-ranking cadre working in a central government ministry. The perception, she explains, is that “women tend not to be willing to work overtime.”

She points out that while women’s overall political representation has improved over the years due to targets and quotas, women still barely figure in positions of Party and government leadership.

For women that do get promoted to leadership positions, they are usually in “feminine” portfolios: women, family, health, welfare. Yet those portfolios are not as valued as “masculine” ones: national security, defence, economics. The implication is that the prospect of promotion for women is often lower. This mirrors social attitudes both inside and outside of China where “feminine” occupations (carers, teachers, nurses) tend to be devalued.

Women in leadership and gender equality bring many benefits to politics as well as society. This is true elsewhere as it is in China.

History

On December 22, 1968, the People’s Daily published a directive by Mao on urban youth:

It is very necessary for the educated youth to go to the countryside and undergo re-education by the poor peasants. We must persuade the cadres and others to send their sons and daughters who have graduated from elementary school, middle school and university to the countryside, let’s mobilise. The comrades in the countryside should welcome them.

知识青年到农村去,接受贫下中农的再教育,很有必要。要说服城里干部和其他人,把自己初中、高中、大学毕业的子女,送到乡下去,来一个动员。各地农村的同志应当欢迎他们去。

What ensued was the massive political and social mobilisation of the Up to the Mountains and Down to the Countryside Movement 上山下乡运动. More than 17 million urban youth (or 10 per cent of the urban population) were sent away to the countryside during the Cultural Revolution decade. Many went willingly to serve the revolution, while others were exiled by the state.

The sent-down youth (or “educated youth” 知识青年) had formed the core of Mao’s ideological shocktroopers in the earlier years of the Cultural Revolution. They were the first generation to have been born and educated under the red flag of the People’s Republic.

Mao had harnessed the idealistic fervour of this generation in political warfare against his enemies within the CCP. But once his enemies fell, the Red Guards had outlived their usefulness. Plus, Mao became disillusioned with their constant infighting. Towards the end of 1968, two years of political turmoil left China’s political and economic institutions in tatters. Schools, government offices, and factories were closed; and there were no opportunities for work or education in China’s cities for its growing youth population.

Mao instructed the sent-down youth to learn revolutionary spirit from the peasants, reform their petty-bourgeois minds, and help build a socialist countryside. But the harsh reality they founded themselves after arriving in the countryside juxtaposed with these lofty ideals. For years, millions of them endured mental and physical hardship in China’s vast rural hinterland and frontier regions. Many young women also experienced sexual harassment, assault, and rape.

It was only after Mao’s death in 1976, and the reinstitution of university entrance exams the following year, that most of the sent-down youth were allowed to return to the cities.

Sent-down mobilisation in the 1960s and 1970s fundamentally changed the life trajectory of a generation of urban youth. It affected most families in China’s cities in some way, including our families.

Today, these sent-down youth are in their mid to late-60s; many are at the pinnacle of their careers. Understanding the historical context for their experience helps us appreciate their world views. In fact, most members of the Politburo Standing Committee hail from that generation. Xi Jinping, for instance, spent his teenage, sent-down years (from 1969 to 1975) in rural Shaanxi province.

Moreover, as we noted last week, “The past is not dead, but alive and used in the present.” On December 22, the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences’ Chinese History Research Institute 中国历史研究院 posted an article on its official WeChat account. This article affirmed the sent-down movement and rebuked critical views:

The Up to the Mountains and Down to the Countryside Movement was a great feat of social progress. The “educated youth” generation is an important cornerstone in the building of the republic. However, for some time now, there have been some views that repudiate the movement. They say nonsense such as that the youths are a "lost generation", that the Movement was a “persecution” and there was “reverse urbanisation”. These opinions are false; there is an ulterior motive in those making them: they are, in fact, attempting to refute the milestones in China’s struggle.

“上山下乡”是推动社会进步的伟大壮举,“知青”是共和国建设的重要基石。然而,一段时间以来,也出现了一些否定“上山下乡”运动的观点。胡说“知青”是“被毁掉的一代”,“上山下乡”是“受迫害”、“逆城市化”等错误言论。这些言论“醉翁之意不在酒”,实际上是企图借此否定新中国的奋斗历程。

Instead, the article implores the reader to interpret history with a “pure heart”.

The meaning and value of the sent-down movement should be viewed from [a correct] historical perspective. Today, China is closer than ever to the far-reaching goal of the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation. Having been baptised and tested by the elements, the sent-down youth will surely become the backbone of this historical process. They will shine radiantly.

知青上山下乡...看待这一问题的意义和价值,时刻不能脱离历史的观点。当今中国比任何时候都更接近中华民族伟大复兴的远大目标,经过风雨洗礼和考验的广大知青,必将在中华民族伟大复兴的历史长河中成为民族的脊梁,放射出灿烂的光芒。

Articles such as this one matter because they signal the attitude of the party leadership to historical events. Today, Beijing is trying to subsume Mao-era history into a narrative of national rejuvenation. The collective memory and trauma of millions of Chinese are glorified as drivers of social progress, paving the road to national greatness. In this story, their sacrifice was worth it because it was for the greater good.

Chinoiserie

Ezra F. Vogel 傅高义 (1930-2020) passed away on December 20 at the age of 90. Professor Vogel is a leading scholar on East Asia. His scholarship has contributed to the understanding of both modern Japan and China. His well-known works include Japan as Number One: Lessons for America (1979), and Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China (2011). In response to the news of his passing, many of his colleagues and acquaintances have spoken of his generosity.

Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs this week declassified and made public about 16,000 pages of documents from 1989. This includes thousands of pages of documents (see Files 11-19) relating to 1989 Tiananmen protests and its aftermath. One document shows Tokyo’s reticence in supporting sanctions proposed by G7 countries in response to Beijing’s violent suppression of protesters. The rationale being that isolating China is not in the long term interest of the West, especially because China was in the process of reform and opening up.

A standout of 2020 Chinese TV hits is The Bad Kids 隐秘的角落, a murder suspense drama that examines childhood trauma and the influence of parents on kids. Beyond the high production value, the show is darker than the average Chinese TV, which normally takes idealistic and heroic themes.

China Story

Joel Wing-Lun, There’s more to Chinese history than the CCP (book recommendations): Checking my phone for COVID updates on Sunday, I was delightfully distracted by Stan Grant’s recommendation that Australians read the 15-volume Cambridge History of China over the summer holidays. As a historian of late imperial and modern China, I couldn’t agree more that there is much to learn about China, and that the legacy of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) is crucial to understanding China today. Yet Cambridge History aside, Grant’s list skews heavily towards Mao and the Chinese Communist Party, when modern Chinese history has been shaped by so much more than that. Might a broader range of titles, and attention to both the rulers and the ruled, help us better understand the superpower with which our future is intertwined?

Andrew Chubb, China warily watches Indian nationalism: India’s Foreign Minister S. Jaishankar said last week that the deadly clashes on the disputed Sino-Indian border this year had “completely changed national sentiment” in his country towards China. There is evidence that Beijing recognises the dangerous double-edged sword of nationalist public opinion in India. So far, this recognition of Indian public opinion’s role in the episode appears to have induced caution from Beijing, but under different circumstances it could lead to escalation.