Neican Briefing is a weekly analysis of China-related current affairs. This series is made possible through the support from the Australian Centre on China in the World, Australian National University.

Subscribe to China Neican and join thousands of policymakers, researchers, and business and media professionals. If you are already a fan, please spread the word:

1. Alibaba fined

Chinese authorities hit Alibaba with a ¥18.2 billion fine on Saturday for abusing its market dominance, restricting competition and stifling innovation.

Last November, Beijing torpedoed Alibaba’s sister firm Ant Group’s IPO at the eleventh hour. In December, the State Administration for Market Regulation announced its investigation of Alibaba.

Alibaba should be counting its stars if this is the end of the story. The fine is small change for the tech giant, only amounting to 4 per cent of its 2019 revenue from China. But more likely Beijing is just getting warmed up.

The Chinese leadership has designated “strengthening anti-monopoly work and preventing disorderly capital accumulation 强化反垄断和防止资本无序扩张” as one of the eight economic policy priorities for 2021. The targets are tech giants that run the most prominent internet platforms in China. Tencent will likely be the next in line to be roughed up.

Beijing’s new zeal for “anti-monopoly” has several drivers. China’s super internet platforms (such as WeChat) pose actual market competition, innovation, and consumer rights issues. More broadly, China is grappling with how to regulate new technology like most countries.

But more interesting for us, this is about political economy. In Xi’s words, “the foundation of [China’s] political economy can only be Marxist political economy, not other economic theories”. In practical terms, this means that “the leading role of the state-owned economy must not be altered.” Beijing’s campaign to rein in China’s tech giants is part of a broader trend towards tighter state control over the economy.

Lastly, and most importantly, it’s about power. The massive power of internet technology to shape public opinion and change the way people live and interact has become clear to the Party leadership. The Communist Party, as an effective monopolist, would be negligent if it doesn’t rush to strangle a potential rival in their crib.

2. Huawei and Ericsson

Huawei’s profit grew by 3.2 per cent last year, despite US sanction. This increase in profit is driven mainly by sales in China. Outside China, its revenue has declined, partly due to the US sanction.

The trend means that Huawei is even more reliant on the domestic Chinese market. It may put less effort into expanding overseas as the US sanctions bite. So sanction has been effective in reducing Huawei profitability and overseas expansion, at least in smartphones.

In a strange twist, Huawei’s chief competitor in 5G, Ericsson, has been lobbying on Huawei’s behalf. The Chief Executive of Ericsson has been pressuring politicians in Sweden to overturn the Huawei ban, from which it directly benefits. Why?

To Ericsson, China is a substantial market as well as a place of manufacturing. So Ericsson’s presence and investment in China made it more likely to align itself with the interests of Beijing, and in this case, by extension, its rival Huawei.

It’s the uncertainty of whether the Chinese Government will ban Ericsson that prompts it to lobby on behalf of Beijing. On the other hand, had Beijing outright banned Ericsson from doing business in China, then Ericsson would have not bothered to please Beijing, since it would have little incentive to.

We saw similar dynamics with Facebook over the last decade. Facebook was actively courting China at one stage, until it realised the futility of its quest. Then, it turned around and lobbied the US Government to be tougher on China.

This shows that governments need to think about the possible perverse incentives that can arise when they block or approve investments.

It is the carrot of hope and the stick of uncertainty in punishment that gives governments power over businesses. But such tactics are harder to implement in a country with robust rule of law, where certainty and consistency are usually the norm.

3. Chinese public & military affairs

The Chinese public’s attitude towards military affairs is often neglected when we talk about China’s military power. Conventional wisdom assumes that public support for the military and its use has shot up in China. But a recent survey by Han Xiao, Michael Sadler and Kai Quek from the University of Hong Kong paints a more complex picture:

Chinese citizens support military spending in the abstract, but their support diminishes when considered alongside other domestic spending priorities...public support for military spending coexists surprisingly with anti-war sentiments and a significant strain of isolationism. In addition, while the conventional wisdom suggests that nationalism moves a state towards bellicosity and war, we find that Chinese citizens with a stronger sense of national pride report stronger anti-war sentiments than other citizens.

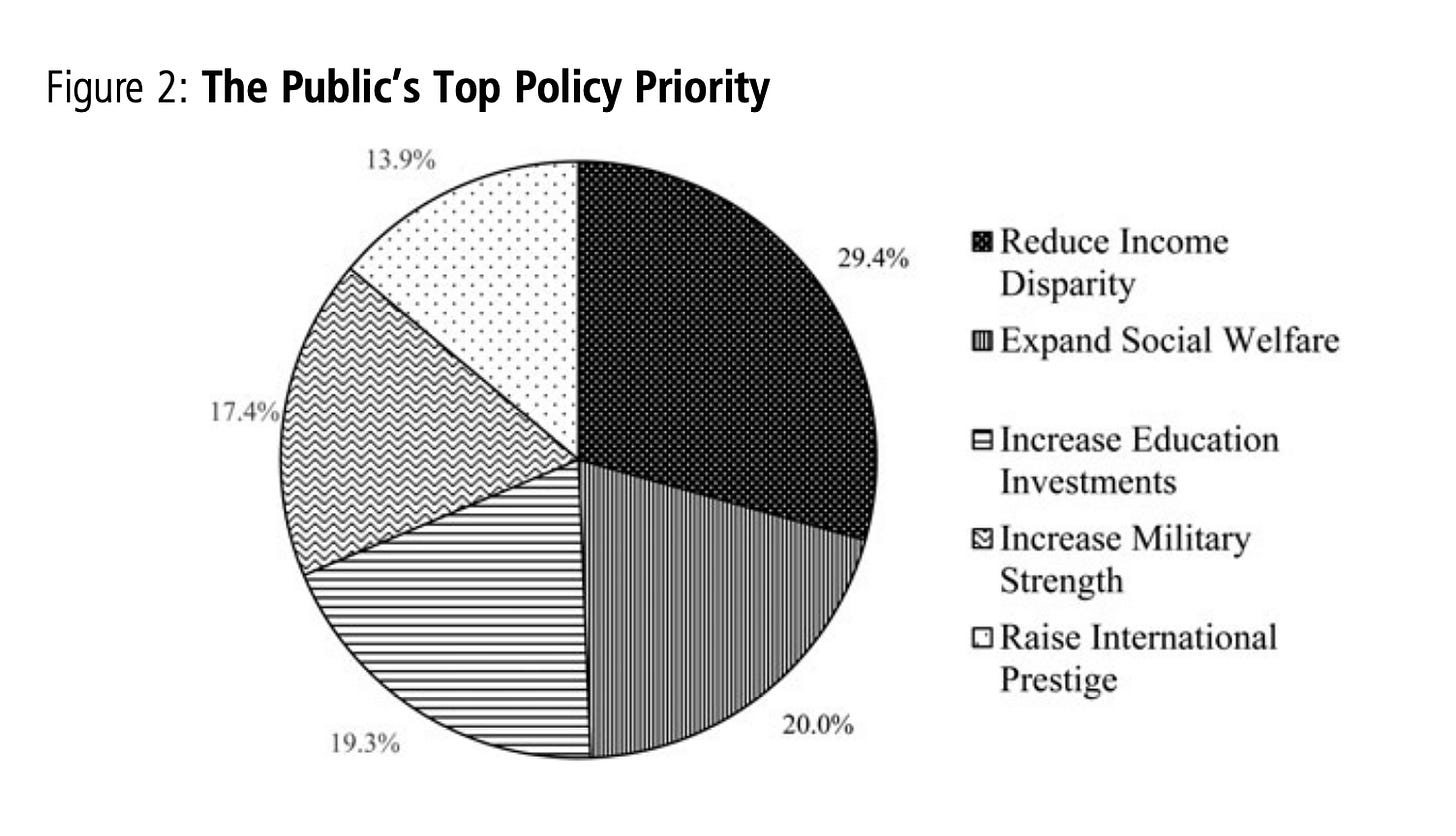

In other words, a majority (55 per cent) wanted higher military spending. But when forced to make “guns vs dumplings” trade-offs, only 17 per cent said the military is a top priority. Income disparity (29 per cent), social welfare (20 per cent) and education (19 per cent) were ranked higher.

War avoidance is the top goal of Chinese foreign policy for 70 per cent of respondents. Only 12 per cent disagreed. And 54 per cent favoured an isolationist foreign policy.

Source: Han, Sadler, and Quek (2021)

As China’s economic growth slows and population ages, the Chinese public will want the government to prioritise social services relative to the military. And their appetite for war and foreign entanglements will be low.

But be warned: panda peace not assured. Public opinion is only one among a number of drivers of Beijing’s policy, and it’s a notoriously fickle one at that.