Neican Brief is a weekly analysis of China-related current affairs. This series is made possible by the support of the Australian Centre on China in the World, Australian National University.

Subscribe to China Neican and join thousands of policymakers, researchers, and business and media professionals. If you are already a fan of what we do, please share it with your friends:

1. Anti-Foreign Sanctions Law

National People’s Congress Standing Committee (NPCSC) passed the Anti-Foreign Sanctions Law《中华人民共和国反外国制裁法》(Chinese | English) on 10 June 2021. The law is effective immediately.

The law provides a legal basis for the Chinese Government to punish and deter those involved in foreign sanctions against China. Individuals and organisations directly or indirectly involved could be subjected to a range of measures, including the denial/revocation of visa, deportation, freezing of assets, and prohibition or restriction on activities and transactions within China.

This law is a response to measures adopted by foreign countries against China, and/or PRC citizens and companies. To Beijing, foreign government criticisms and/or sanctions concerning Xinjiang, Hong Kong, Taiwan, South China Sea, and other issues, are deplorable interference in China’s internal affairs. In the words of one senior official from the NPCSC’s Legislative Affairs Commission:

certain Western countries and organizations have been unwilling to acknowledge and accept the reality of China's...progress. Out of political manipulation and ideological prejudice, they have used various issues and pretexts...to make accusations, smear and attack China...contain and suppress China's development, and in particular...by imposing so-called “sanctions” on relevant Chinese state organs, organisations and state officials in accordance with their own laws, and have violently interfered in China's internal affairs.

We should interpret the Chinese word for “sanctions”, 制裁, broadly when thinking about the kind of activities that it targets. It targets recent Western sanctions relating to Xinjiang and Hong Kong. But it would, in our view, include, for example, restrictions by foreign governments against Huawei and other Chinese companies.

Individuals and organisations (eg., financial institutions) implementing, or are involved in, foreign sanctions against China, now face a higher risk of punishment by the Chinese government.

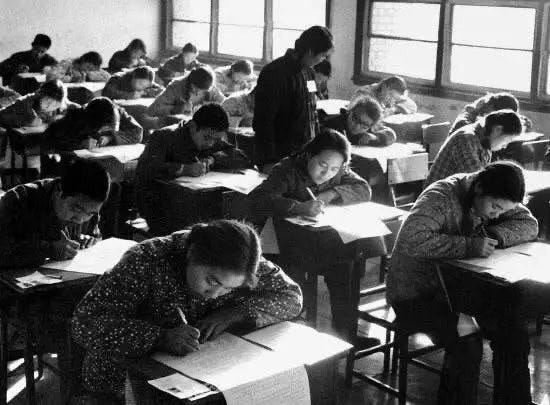

2. Gaokao

China’s Gaokao (National College Entrance Examination) was held across the country from Monday to Thursday this week. A record 10.8 million Chinese students sat the exams this year.

The students are under intense pressure to do well, both from themselves and their parents. For the parents, years of 心血 “heart and blood” (that is, hard work, sacrifice, anxiety and hope) boils down to these exams.

Gaokao is widely considered to be one of the most important events in a person’s life, on par with marriage. Gaokao determines what kind of higher education they have access to, and this in turn can determine what kind of job they can get when they graduate.

In China’s ultra competitive society, education credentials are widely seen as a ticket to upward social mobility.

In dynastic China, many families would put all their resources into educating one of their kids in the hope they would pass the imperial exams and become a state bureaucrat. The rise and fall of families depended on the success or failure of this project. The contemporary version of this is Gaokao.

On a personal note, the resumption of Gaokao in 1977 was monumental for China, and it changed the trajectories of our respective families. That year, 5.7 million people participated and the admission rate was under 5 per cent (compared to around 80 per cent for recent years). Both of our parents were successful. If they did not, our lives would have been very different.

Adam’s dad described it as “carps jumping over the Dragon Gate” 鲤鱼跳龙门. Imagine salmon trying to leap up a waterfall on their way to upriver breeding grounds. Whether they can leap over the threshold or not is of profound and lasting significance.

3. Vocational education reform

Staying on the topic of education…

Students from Nanjing Normal University Zhongbei College 南京师范大学中北学院 protested on Sunday (6 June) plans to merge their college into Nanjing Commerce Vocational and Technical University 南京经贸职业技术大学. The students allegedly took the head of the college hostage for 30 hours and clashed with police.

This is not an isolated incident. Large scale protests (by students and parents) for the same reason have occurred in Zhejiang and Guizhou provinces.

For background, in China’s education system there are “independent colleges” (独立学院) attached to some public universities. These are joint projects by universities and private capital, usually for profit. Compared to public universities, their entrance requirements are lower, but they are much more expensive to attend. Students graduate from these colleges with “standard bachelors” 普通本科.

In January 2019, the State Council issued a blueprint to reform China’s vocational education system. The reform aims to tackle China’s shortage of technical specialists, which according to one estimate, amounts to a shortage of 20 million.

As part of broader reform, the Ministry of Education issued an implementation plan in May 2020 to accelerate the program to transfer “independent colleges” attached to normal universities to vocational universities. This was widely viewed as an ultimatum for local authorities and schools to stop dragging their feet.

Many students have protested because they thought that once the transfer has been complete, their qualification upon graduation would be downgraded from “standard bachelor” to “vocational bachelors” 职业本科. The Ministry of Education has issued a statement pointing out that this would only apply to future and not current students.

The recent protests have led to the temporary suspension of plans to merge independent colleges into vocational education institutions, including in Zhejiang and Shandong.

One key underlying problem is that students, parents and employers preferred education qualifications from universities. Technical trades and credentials from vocational education institutions are often seen as inferior and not a ticket to high income and respectability.

4. Industry policy

Do you remember Made in China 2025, supposedly China’s grand strategy to take over the tech world by 2025? Its industry-support and state-intervention initiatives were roundly criticised by other countries, as it led to what the US said was unfair advantage.

But in the US, a bipartisan consensus is emerging that in order to compete with China, industry policy and state intervention is necessary, and market forces alone are not enough.

This week, the US Senate passed the US Innovation and Competition Act (also known as Endless Frontier Act), which includes hundreds of billions of dollars investment in science and technology, and $52 billion subsidies to semiconductor makers. The bill has not yet passed in the House.

Large scale state intervention in technology has precedence: during the Cold War, the US Government spent a huge amount of money on science and technology, especially in military-related fields, in an arms race with the Soviet Union.

So apart from intensifying competition between China and the US in technology, what does it mean for other countries?

Such grand investment by the US Government could be good news for other countries, especially consumers of technology. If both the US and China are subsidising technology innovation and production, then consumers of technology in other countries — both individuals and governments — could be paying less for the subsidised technology.

Effectively, taxpayers in the US and China are subsidising consumers of technology elsewhere. Even though subsidies are generally market-distorting, it can benefit consumers at the expense of producers. So producers of technology elsewhere (e.g. Europe and Japan) might be worse off as they become less competitive compared to American and Chinese producers.

All this assumes that the technology remains a competitive market. But the reason why the US and China are willing to pour money into this is that they think whoever wins this competition can set standards for the future and become the dominant player. This will give them an opportunity to recoup their initial investment down the track.

In any case, this proposed legislation is another reminder that the argument for state intervention has become louder across the world, even in those countries that profess beliefs in the free market.

When it comes to great power competition, the urge is still to look to state intervention rather than leaving it to the markets.

5. Elephant journey

A herd of elephants on a long journey far away from their natural habitat has, unsurprisingly, captivated social media in China. It has prompted some discussions online of habitat destruction.

They have now arrived near Kunming. But we just want to share the photo of the herd (and point out that they are “laying down” for a rest).